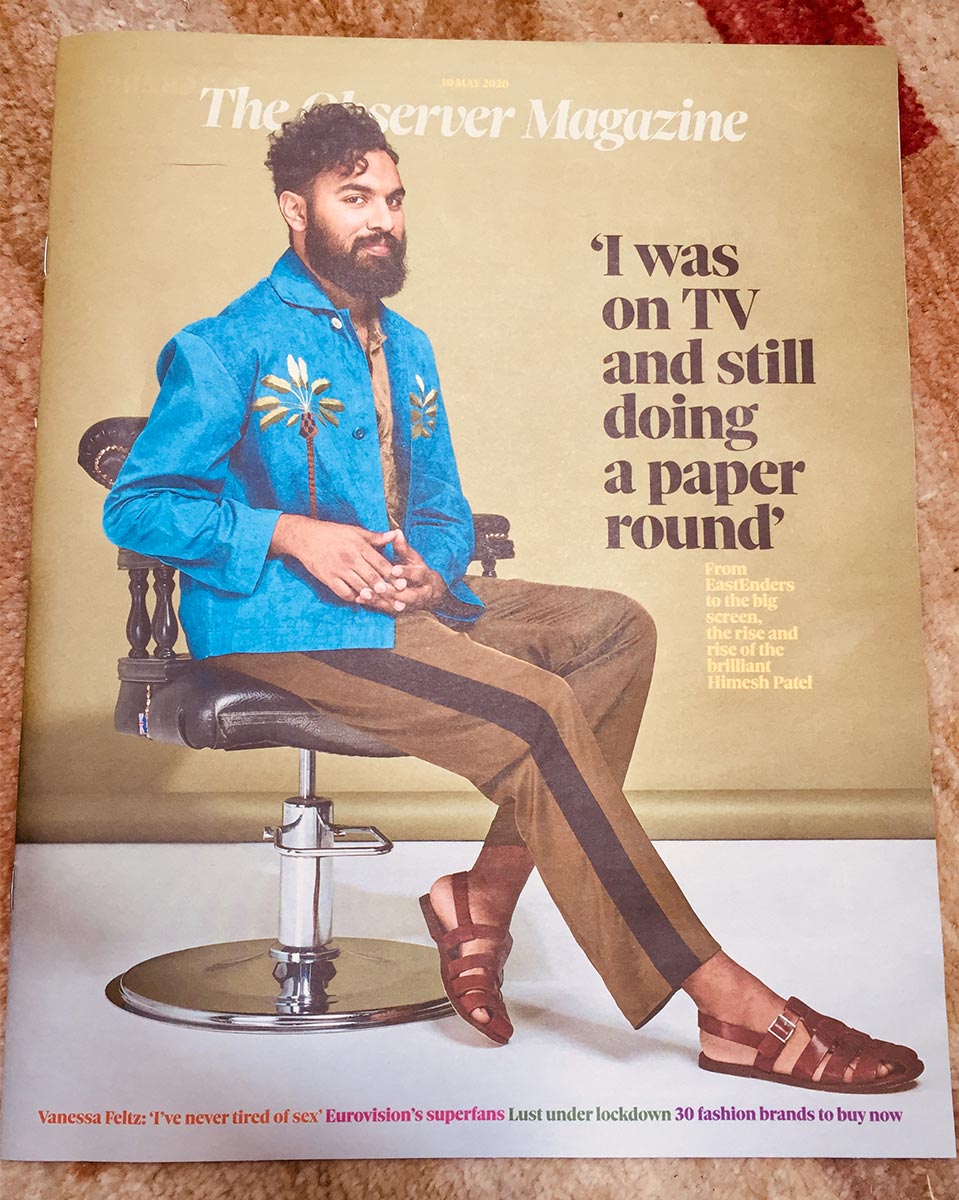

Himesh (Patel) featured in this Sunday’s Observer Magazine – photos below and the full article from the Observer website: https://www.theguardian.com/global/2020/may/10/himesh-patel-it-felt-odd-making-a-show-about-a-pandemic

The former EastEnders actor talks about shooting a pilot on a deadly virus, telling British stories with a difference – and how playing a bit part as a pigeon changed his career

Sam Wolfson

Sun 10 May 2020

The so-called “curse of EastEnders” – the struggle for soap actors to transition into more prestigious dramatic roles after leaving the show – always weighed heavily on the mind of Himesh Patel.

So when he decided to leave the soap in 2016, after nine years playing Tamwar Masood, he knew whichever role he chose next would be critical in breaking typecast, perhaps even defining the rest of his career. He went to a friend whose theatre company, withWings, took inventive musical adaptations to the Edinburgh fringe. That year they were doing Le Bossu, a retelling of The Hunchback of Notre Dame. Patel mentioned that he wanted to get out of his comfort zone and do some theatre.

He came back to me and said, ‘Cool, well, I can offer you the role of a pigeon.’”

Most actors who had spent their lives being watched by 8m viewers, four nights a week, would be unwilling to start again at the bottom rung of acting. (The pigeon was a bit part.) But Patel, now 29, leapt at the chance.

And, honestly, playing that pigeon, for so many reasons, was one of the most important things I ever did. I remember that feeling being side of stage as the lights went down – that fear was so visceral. Then, as the run went on, it slowly ebbed away. It let me become a more extroverted performer, which set me up for what came next.”

What came next was a starring role in Danny Boyle’s counter-factual caper Yesterday, in which Patel stars as Jack Malik who, after a freak thunderstorm, is the only person on earth who remembers the music of the Beatles. Malik becomes a star overnight, plays Wembley with Ed Sheeran, and is hailed as the greatest songwriter of his generation. The film transformed Patel’s life with similar force. His follow-up roles have all screamed prestige: leading turns in Armando Iannucci’s sci-fi spoof Avenue 5 and the BBC’s adaptation of Eleanor Catton’s The Luminaries, the 2013 novel, set in the New Zealand goldrush.

He’s recently arrived back from Chicago, where he shot the pilot for HBO’s adaptation of Station Eleven, the Emily St John Mandel novel about, eerily, a flu pandemic that wipes out 90% of the world’s population. When Patel started shooting, he was most concerned about how freezing Illinois gets in January. Then, as more news came from China, the strangeness of the situation started to sink in.

The episode we filmed was the beginning of the outbreak. It felt incredibly odd, making a show about a global pandemic, and now here we are.”

The oddest moment, he says, was finding out that production of a series about a pandemic was now on hold because of a pandemic.

We meet on a weekday lunchtime at a pub in Islington, London in that eerie period before the enforced lockdown when pubs and restaurants are still open but people are furiously washing their hands and firing evil glares at anyone clearing their throat. The pub has posters declaring that the toilet doors have been jammed open so you don’t have to touch any handles. It means the faint sound of ablutions can be heard throughout our conversation.

Patel arrives straight from the photoshoot, an experience he tentatively enjoyed. His parents own a newsagents in the small village of Sawtry, near Cambridge, and he likes knowing that they’ll get the papers in one morning and see photos of him looking suave. He hasn’t always been a fan of Sunday supplements. As a teenager, he had to help out his folks by doing the local paper round. Weekends, he says, were always the worst.

The papers were full of magazines! So I’d have to walk up the hill, then go back down, and then go further up the hill because you can’t carry them all at once.”

His childhood days were crammed.

As well as school and the paper round, he went to several different drama schools. He giggles when I ask what it was that set apart the kinds of kids he met at those after-school classes.

We were all a bit odd, mimicking things we’d seen on telly, creating these little pop-culture storms within our own lives. Maybe some of us were quite attention-hungry, but we were alive with this energy. It’s the antithesis of a maths lesson. It’s about play.”

He was 16 when a new executive producer on EastEnders, Diederick Santer, began an overhaul of the families on the soap to make it “feel more 21st century”. That included introducing a Pakistani family on the show, the Masoods. Patel was nervous in the audition for Tamwar Masood and thought he’d ruined his chances when he told producers he didn’t really watch the show. But they saw something in him and, once on board, he went about turning Tamwar into one of the most unusual characters in soap. He was removed and analytical. He existed almost outside the show, a kind of geeky flaneur who saw the absurdity of Albert Square in the same way the audience did. In a show that’s always been about dramatic bust-ups and big acting, Patel played against the action: quiet and pitying, often lingering in the back of someone else’s family crisis. Patel quickly became a fan favourite. His character’s marriage to Afia Khan (Meryl Fernandes) won the pair Inside Soap award for best wedding.

His parents, though proud, were also insistent that the paper round must continue. “Those were the days,” he says.

I’d be, like, ‘It’s the weekend, I’m trudging round the village in the rain, why am I having to do this?’ But I look back on it fondly. It was important for me to be on national TV and be doing a paper round at the same time. It was just a daily reminder of being brought back down to earth.”

By his mid-20s, Patel was beginning to look at the career paths available to him.

There’s a thin line between being on a soap and being a celebrity. You often see people from EastEnders going to do I’m a Celebrity or Strictly – which is great if that’s what you want to do. But from going to a lot of these awards ceremonies, it wasn’t somewhere I was ever going to enjoy myself.”

He said the decision to leave was both easy and scary.

I’d been doing it since I was 16 and it was all I’d known as an adult. It was a leap of faith. I remember on that last day I drove out the gates that last time, and I just thought: here we go, let’s see what happens.”

His certainty about wanting to do something more than Strictly is the result of his particular upbringing, he says. The closest town growing up was Huntingdon, in the heart of John Major’s old constituency. (Patel’s mother would always point out his house when they drove past.) He didn’t have any traumatic experiences of racism growing up,

but there were very few people who looked like me and there is a part of you that you consciously or subconsciously dilute in order to fit in. There are a lot of feelings that I grew up with that I later started to realise I wasn’t alone in feeling, and that perhaps there’s something to be done about that.”

His adolescence left him with a dogged feeling of responsibility – to make it easier for the next generation of kids like him. He talks about “responsibility” a lot.

I suppose it’s the responsibility, as someone British, to say: ‘This is also British, the story that I’m telling you about my parents, or Indian soldiers that fought in the world wars.’ These stories are also British. At a time when people want to limit the idea of Britishness, physically speaking, I think I’d quite like to broaden it.”

He gives the example of Britain’s colonial history in India, something he feels mainstream Britain has never properly wrestled with.

We watched a lot of Indian movies growing up, and every now and then there’d be one about British rule, but I never really learned about that in school. So there was a disconnect between these films I was watching, set during a very turbulent time in India’s history, and school, where we might be taught that Gandhi was a liberator, but not what he was liberating from.”

He’s not angry at people who haven’t taken the time to learn that history, he says, but he sees his role as bringing those stories to them. He talks about watching Saving Private Ryan in history class, how it brought to life a war he would have otherwise struggled to imagine.

One of the most powerful ways of finding out about stuff is TV and film. If I can, in my current position, get the ball rolling on some of those stories then I’d really like to do that.”

(He says he has writing and acting projects in the works that would fulfil that brief.)

It’s a sense of duty that imbues much of Patel’s life. Even when we’re talking about The Luminaries, in which he plays Emery Staines, a young prospector, conversation veers back to the importance of minority stories in national history. During the six months he spent in New Zealand filming the show, which will air later this year, he was impressed by the public’s understanding of a wide range of historical events.

I fell in love with the culture. For a country that was a colonial outpost, as it were, they’ve really made efforts to integrate the indigenous Māori culture. The country is not without its troubles, but we went up to Waitangi, where the British signed a treaty with the Māori, and even just tiny gestures, like the signs being both in English and in Māori. A lot of people who I met who were not of Māori descent were just as aware of that history, which was commendable.”

One concrete change he is trying to make is through his membership of Bafta, which was heavily criticised for all-white shortlists in a number of award categories. Patel was one of several actors who offered alternative shortlists in protest:

The oddity for me is how an amazing film such as Parasite did so well and yet none of the actors got nominated.”

I ask whether he ever feels annoyed having to hand over his annual Bafta membership fee (not cheap at £495), when the awards fail to recognise diverse talent again and again. Does there ever come a point where the institutions themselves should be left to fail?

I know some people feel like that, but I don’t think I’m there yet because the impact of things like the Baftas is still huge. I grew up in a rural place, naive to how a lot of the industry works. For me watching the Baftas was a big deal. When Slumdog Millionaire won all those awards I thought, wow it’s relevant on that level. So now I’m a member I want to change things from the inside.”

Patel has a persistent seriousness about him. His manner is more that of an activist: dogged and thoughtful. The paper round, the pigeon, the desire to make movies that get shown in a classroom… it all reflects a person entirely uninterested in flashness. We all want to be seen as compassionate, but surely he has moments of indulging his new wealth and celebrity? What’s been his most lavish purchase?

Mmm, well recently I kept seeing Teslas everywhere, so I did have a brief look at their website kind of going, ‘Well, it’s good for the planet isn’t it?’ But it is still very expensive. And I live in London, so I don’t need a car.”

Instead, he says, he bought a new camera.

My dad always had cameras around. I like the very quiet way of saying things through photography. There’s something about the ambiguity, and the silence of a photo…”

I am convinced, with the sombreness of this remark, this is the real Himesh.

Leave a Reply